History

St. Stephen’s College was founded in 1903 as a Christian school for Chinese boys. By 1928 it had out grown its original site on Bonham Street and moved to Stanley. The College was modelled on English Public Schools and became known as the “Eton of the East”.

All of that changed with the coming of the Second World War and the Japanese invasion of Hong Kong in December 1941. The battle for Hong Kong was bitterly fought with heavy casualties on both sides. St. Stephen’s was pressed into service as a military hospital, but on Christmas Day the College became a battleground. The invading Japanese troops stormed into the College and massacred up to 60 wounded soldiers in their beds, along with doctors and nurses who tried to protect them.

Following the British surrender, St. Stephen’s became an internment camp for the Allied civilians until the war ended in 1945. The hardship, suffering and spirit of those times is reflected in the memorial window over the door of the Chapel. We still receive visits from people who were interned here and their families.

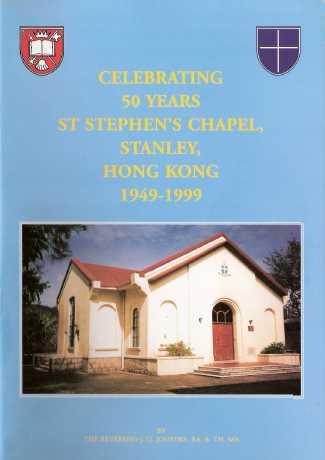

The Chapel itself was built after the war. The Foundation Stone was laid by Bishop R.O Hall on 10th December 1949 and the Chapel was consecrated on 4th March 1950. During the consecration, Bishop Hall dedicated the Chapel to those who died in the war and those who suffered here during the internment. We remember them on Remembrance Sunday in November every year.

|

|

As well as being the School Chapel, since 1977 it has also been home to the present English speaking congregation as a daughter church of St. John’s Cathedral

A history booklet of the Chapel was published in 1999.

|

Remembrance Sunday, 13th November 2011

Sermon at St Stephen’s, Stanley

Today is Remembrance Sunday. The red poppies that many of us are wearing recall the fields of Flanders, the trenches of the 1st World War, and the day when the war stopped and the guns fell silent – at the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month, 1918.

Here in St Stephen’s Stanley today we remember especially victims of another war, the 2nd World War. When the Japanese invaded Hong Kong, the last desperate battle was fought here on Christmas Day 1941. It’s hard to imagine that the beautiful, peaceful college campus we know today was littered then with dead bodies, Allied and Japanese. This year is the 70th anniversary of the Battle of Hong Kong. During the years of occupation which followed, St Stephen’s College became the internment camp for allied civilians, men, women and children.

At that time this chapel did not exist. It was built after the war, and dedicated by Bishop R O Hall, Bishop of Hong Kong, to those who died in the war and those who suffered here during the internment. The chapel still carries reminders of those days.

Above the door of the chapel is a memorial window. The main picture shows a scene from life in the internment camp. It’s a church service. The man on the right is holding a bible in his hand and preaching to the thin, undernourished internees before him. In the background are the school buildings, the same ones that are still standing in the centre of the college. To the left you can see reproductions of two documents from the camp, a list of names and a calendar. They are a record of several men in the camp and the date when they were executed by the Japanese authorities. They had been caught secretly listening to an allied radio broadcast. There was no defence.

But the window shows not only the dark side of camp life. Above the main image is a smaller picture, of children sitting on steps, waving. That image is from a photo taken on Liberation Day in August 1945, when the war was over and the children were free to leave the camp at last. Only last month an Englishwoman visited the Chapel and told me that one of those children was her brother. On either side of the scene, two images of a dove represent the Holy Spirit. Local flowers surround the picture – the bauhinia, hibiscus and frangipani. Their significance is explained in the inscription at the top of the arch: ‘This window is dedicated to the memory of those who died at Stanley 1941-45. Their Spirit, Hope, Faith & Love will, as the flowers living cycle, remain to refresh us always.’

And the Chinese characters in the middle of the window are the characters for Faith, Hope and Love – the great virtues praised by St Paul in writing to the Corinthians.

Two other items here are also memorials of the war in Hong Kong. The plaque fixed to the wall under the wooden cross lists the officers and men of the Royal Artillery, stationed at Stanley Fort, who lost their lives in the war. Many died on October 2nd 1942 when the Lisbon Maru, the ship carrying them to labour camps in Japan was sunk off Shanghai. The plaque was originally in St Barbara’s, the Stanley Fort garrison church, and was moved here in 1997 when St Barbara’s was closed.

And the brass cross which stands behind the altar came from a church which no longer exists, the Peak Chapel. The Peak Chapel was destroyed during the war, and this cross was rescued from the ruins and brought to Stanley, where it was used in services in the internment camp. This more than anything else I’ve spoken about, brings us directly into contact with those who endured and prayed here during the war, and looked to that cross, the symbol of their faith, as we look to it now.

Some of them did not survive. They are remembered now in the names on the gravestones in the beautifully-maintained military cemetery behind the college. Later this morning we will lay a wreath of poppies there and remember them, as we do every year. But others did survive, sustained by the spirit of hope, faith and love.

Every year a group of students from a Japanese School visit St Stephen’s. They come to this chapel, and I tell them the story of what happened here. One year, after I spoke to them, the students conferred together and then one of them stood up and said, ‘We want to apologise for the actions of our ancestors.’ I was very deeply moved. We often hear that the Japanese do not apologise for atrocities during the war, but here were young Japanese students doing exactly that.

Remembering is at the heart of our Christian faith. Right at the centre of our church services, week by week, we remember another terrible act of violence, the torture and death of an innocent young man – Jesus of Nazareth. We remember because he told us to: he said ‘Do this in remembrance of me’. And we also remember because we believe that Jesus’ life, death and resurrection brings hope to despairing lives and healing to a suffering world.

Amen.

Remembrance Sunday Wreath Laying in Stanley Military Cemetery